|

Home

Boris Sidis Archive Menu Table

of Contents

Next Chapter .pdf

(Book)

PART II THE SELF

CHAPTER X THE SECONDARY SELF THE law of suggestibility in general, and those of normal and abnormal suggestibility in particular, indicate a coexistence of two streams of consciousness, of two selves within the frame of the individual; the one, the waking consciousness, the waking self; the other, the subwaking consciousness, the subwaking self. But although the conditions and laws of suggestibility clearly point to a double self as constituting human individuality, still the proof, strong as it appears to me to be, is rather of an indirect nature. We must therefore look for facts that should directly and explicitly prove the same truth. We do not lack such facts. We turn first to those of hysteria. If we put a pencil or scissors into the anæsthetic hand of the hysterical person without his seeing it, the insensible hand makes adaptive movements. The fingers seize the pencil and place it in a position as if the hand were going to write. Quite differently does the hand possess itself of the scissors: the hand gets hold of the instrument in the proper way, and seems ready for work, for cutting. Now all the while the subject is totally unconscious of what is happening there to his hand, since it is insensible, and he can not possibly see it, as his face is concealed by a screen. It is obvious that in order for such movements of adaptation to occur that there must be recognition of the object kept by the anæsthetic hand. But recognition requires a complex mental operation: it requires that the object should be perceived, should be remembered, and should be classed with objects of a certain kind and order. The very fact of the adaptation movements indicate the presence of some kind of embryonic will. Simple as these experiments are, they none the less strongly indicate the presence of a hidden agency that works through the anæsthetic hand; an agency that possesses perception, memory, judgment, and even will. Since these operations are essentially characteristics of consciousness, of a self, we must necessarily conclude that it is a conscious agency that acts through the insensible hand of the hysterical person. Since the activity of this intelligence, simple and elementary as it is, is unknown to the subject, it is quite clear that there is present within him a secondary consciousness standing in no connection with the primary stream of personal consciousness, and somehow coming in possession of the person's hand. As we advance in our research and make the conditions more and more complicated, all doubt as to the presence of a conscious being, behind the veil of the subject's primary consciousness, completely disappears. "We put a pen," says Binet1 "into the anæsthetic hand and we make it write a word; left to itself, the hand preserves its attitude, and at the expiration of a short space of time repeats the words often five or ten times. Having arrived at this fact, we again seize the anæsthetic hand and cause it to write some familiar word―for example, the patient's own name―but in so doing we intentionally commit an error in spelling. In its turn the anæsthetic hand repeats the word, but, oddly enough, the hand betrays a momentary hesitation when it reaches the letter at which the error in orthography was committed. If a superfluous letter happens to have been added, sometimes the hand will hesitatingly rewrite the name along with the supplementary letter; again, it will retrace only a part of the letter in question; and again, finally, entirely suppress it." It is quite evident that we have here to deal with a conscious agent hesitating about mistakes and able to correct them; we can not possibly ascribe such activity to mere unconscious cerebration. If again we take the anæsthetic hand and trace on the dorsal side of it a letter or a figure, the hand traces this figure or letter. Evidently the secondary consciousness is in full possession of these perceptions, although the primary consciousness of the subject is totally ignorant of them. Furthermore, insensible as the anæsthetic hand is, since no pinching, pricking, burning, or faradization of it are perceived by the subject, still we can show that there exists a hidden sensibility in the hand; this can easily be proved by the æsthesiometer. If we prick the insensible hand with one of the points of a pair of compasses, the hand automatically traces a single point. Apply both points, and the automatic writing will trace two points, thus informing us of its degree of insensibility. The amaurotic or hysterical eye gives us still stronger evidence of the existence of a secondary being perceiving things which lie outside the visual distance of the subject's waking consciousness. Hysterical subjects often complain of the loss of sight. As a matter of fact, when we come to test it we find that the subject does see what he claims not to see. This is detected by the so-called "box of Flees." This box is so skilfully arranged that the patient sees with his right eye the picture or the figure situated to the left, and with his left eye what is situated to the right. The hysterical person blind in the right eye, when put to such a test, declares that he sees the picture to the left side but not that to the right. He sees with the blind eye. Amaurosis may also be tested in a somewhat different way. A pair of spectacles in which one glass is red and the other green is put on the patient's eye, and he is made to read six letters on a blank frame, alternately covered with red and green glass. When one eye is closed only three letters can be seen through the spectacles―namely, the ones corresponding in color to the spectacle glass through which the eye is looking; the other three can not be seen on account of the two complementary colors forming black. The patient, then, blind in one eye (say the right), ought to see only three letters when he has the spectacles on. When, however, put to this test the patient promptly reads the six letters. The right eye undoubtedly sees, only the image is retained by the secondary self, and a special arrangement of conditions is required to force that hidden self to surrender the image it stole. To reveal the presence of this secondary self that perceives and knows facts hidden from the upper consciousness or primary self, I frequently employ the following simple but sure method, which may be characterized as the method of "guessing": Impressions are made on the anæsthetic limb, and the subject who does not perceive any of the applied stimuli is asked just to make a "wild guess" as to the nature and number of the stimuli, if there were any. Now the interest is that nearly all the guesses are found to be correct. Dr. William A. White, of Binghamton State Hospital, finds that this method works well in his cases. "In the case of D. F.," Dr. White writes to me, "whose field of vision I sent you, I find by experiment, taking a hint from you, that, by introducing fingers between the limit of her field of vision (which is very contracted) and the limit of the normal field, she could guess each time and tell which finger was held up." To bring out still more clearly and decisively the presence of a secondary consciousness that perceives the image which the hysterical person does not see, A. Binet performed the following experiment: "We place," he says,2 "the hysterical subject before a scale of printed letters, and tentatively seek the maximum distance from the board at which the subject is able to read the largest letters. After having experimentally determined the maximum distance at which the subject can read the largest letters of the series, we invite him to read certain small letters that are placed below the former. Naturally enough, the subject is unable to do so; but if at this instant we slip a pencil into the anæsthetic hand, we are able by the agency of the hand to induce automatic writing, and this writing will reproduce precisely the letters which the subject is in vain trying to read. It is highly interesting to observe that during the very time the subject is repeatedly declaring that he does not see the letters, the anæsthetic hand, unknown to him, writes out the letters one after another. If, interrupting the experiments, we ask the subject to write of his own free will the letters of the printed series, he will not he able to do so: and when asked simply to draw what he sees, he will only produce a few zigzag marks that have no meaning." These experiments plainly prove that the secondary consciousness sees the letters or words, and directs the anæsthetic hand it possesses to write what it perceives. Furthermore, if we remove the subject at too great a distance, so that the letters are altogether out of the range of vision of the secondary consciousness, the automatic writing begins to make errors―writing, for instance, "Lucien" instead of "Louise"; it tries to guess. Now if anything plainly shows the presence of a hidden intelligence, it is surely this guessing of which the subject himself is totally unconscious, for guessing is essentially a characteristic of consciousness. "An automaton," truly remarks Binet, "does not mistake; the secondary consciousness, on the contrary, is subject to errors because it is a consciousness, because it is a thing that reasons and combines thoughts." This last conclusion is still further proved by the following experiments: "There are patients," writes Binet3 "(St. Am., for example), whose hand spontaneously finishes the word they are made to trace. Thus I cause the letter 'd' to be written; the hand continues and writes 'don.' I write 'pa,' and the hand continues and writes 'pavilion.' I write 'Sal,' and the hand writes 'Salpêtrière.'" Here it is still more obvious that we are in the presence of a hidden agency that can take hints and develop them intelligently. We saw above that distraction of attention is one of the indispensable conditions of suggestibility in the normal waking state. Now, M. Janet, in his experiments on hysterical persons, used chiefly this condition, or (as it may be called) "method of distraction," as a means for coming into direct oral communication with the secondary suggestible self. In hysterical persons it is easier to bring about the conditions of suggestibility, because, as a rule, they possess a contracted field of consciousness, and when engaged in one thing they are oblivious to all else. "When Lucie [the subject] talked directly with anyone," says M. Janet,4 "she ceased to be able to hear any other person. You may stand behind her, call her by name, shout abuse in her ear, without making her turn round; or place yourself before her, show her objects, touch her, etc., without attracting her notice. When finally she becomes aware of you she thinks you have just come into the room again, and greets you accordingly." M. Janet availed himself of these already existent conditions of suggestibility, and began to give her suggestions while she was in the waking state. When the subject's attention was fully fixed on a conversation with a third party, M. Janet came up behind her, whispered in her car some simple commands, which she instantly obeyed. He made her reply by signs to his questions, and even made her answer in writing if a pencil were placed in her hands. The subject's primary consciousness was entirely ignorant of what was going on. In some cases the patient was made to pass through a series of awkward bodily positions without the least spark of knowledge on his side. The following is a very interesting and striking case: P., a man of forty, was received at the hospital at Havre for delirium tremens. He improved and became quite rational during the daytime. The hospital doctor observed that the patient was highly suggestible, and invited M. Janet to experiment on him. "While the doctor was talking to the patient on some interesting subject," writes M. Janet,5 "I placed myself behind P., and told him to raise his arm. On the first trial I had to touch his arm in order to provoke the desired act; afterward his unconscious obedience followed my order without difficulty. I made him walk, sit down, kneel―all without his knowing it. I even told him to lie down on his stomach, and he fell down at once, but his head still raised itself to answer at once the doctor's questions. The doctor asked him, 'In what position are you while I am talking to you?' 'Why, I am standing by my bed; I am not moving.'" The secondary self accepted motor suggestions of which the primary self was totally unaware. As the orders thus whispered to the secondary, subwaking self become more complicated the latter rises to the surface, pushes the waking self into the background and carries out the suggested commands. "M. Binet had been kind enough," writes M. Janet,6 "to show me one of the subjects on whom he was in the habit of studying acts rendered unconscious by anæsthesia, and I had asked his permission to produce on this subject the phenomenon of suggestion by distraction. Everything took place just as I expected. The subject (Hab.), fully awake, talked to M. Binet. Placing myself behind her, I caused her to move her hand unconsciously, to write a few words, to answer my questions by signs, etc. Suddenly Hab. ceased to speak to M. Binet, and, turning toward me, continued correctly by the voice the conversation she had begun with me by unconscious signs. On the other hand, she no longer spoke to M. Binet, and could no longer hear him speak; in a word, she had fallen into elective somnambulism (rapport). It was necessary to wake her up, and when awakened she had naturally forgotten everything. Now Hab. had no previous knowledge of me at all; it was not, therefore, my presence which had sent her to sleep. The sleep was in this case manifestly the result of the development of unconscious actions, which had invaded and finally effaced the normal consciousness. This explanation, indeed, is easily verified. My subject, Madame. B——, remains wide awake in my neighbourhood so long as I do not provoke unconscious phenomena, but when the unconscious phenomena become too numerous and too complicated she goes to sleep." We have here clear and direct proof as to the presence of a conscious agency lying buried below the upper stratum of personal life, and also as to the identity of this hidden, mysterious self with the hypnotic self. The self of normal and that of abnormal suggestibility are one and the same. Turning now to hypnosis, we find that the classical experiments of P. Janet and Gourney on deferred or post-hypnotic suggestion furnish clear, valid, and direct evidence of the reality of a secondary consciousness, of an intelligent, subwaking, hypnotic self concealed behind the curtain of personal consciousness. "When Lucie was in a state of genuine somnambulism," writes P. Janet, "I said to her, in the tone used for giving suggestions, 'When I clap my hand twelve times you will go to sleep again.' Then I talked to her of other things, and five or six minutes later I woke her completely. The forgetfulness of all that had happened during the hypnotic state, and of my suggestion in particular, was complete. I was assured of this forgetfulness, which was an important thing here, first, by the preceding state of sleep, which was genuine somnambulism with all its characteristic symptoms; by the agreement of all those who have been engaged upon these questions, and who have all proved the forgetfulness of similar suggestions after waking; and, finally, by the results of all the preceding experiments made upon this subject, in which I have always found this unconsciousness. Other people surrounded Lucie and talked to her about different things; and then, drawing back a few steps, I struck my hand five blows at rather long intervals and rather faintly, noticing at the same time that the subject paid no attention to me, but still talked on briskly. I came nearer and said to her, 'Did you hear what I just did?' 'What did you do?' said she, 'I was not paying attention.' 'This' (I clapped my hands). 'You just clapped your hands.' 'How many times?' 'Once.' I drew back and continued to clap more faintly every now and then. Lucie, whose attention was distracted, no longer listened to me, and seemed to have completely forgotten my existence. When I had clapped six times more in this way, which with the preceding ones made twelve, Lucie stopped talking immediately, closed her eyes, and fell back asleep. 'Why do you go to sleep?' I said to her. 'I do not know anything about it; it came upon me at once,' she said. "The somnambulist must have counted, for I endeavoured to make the blows just alike, and the twelfth could not be distinguished from the preceding ones. She must have heard them and counted them, but without knowing it; therefore, unconsciously (subconsciously). The experiment was easy to repeat, and I repeated it in many ways. In this way Lucie counted unconsciously (subconsciously) up to forty-three, the blows being sometimes regular and sometimes irregular, with never a mistake in the result. The most striking of these experiments was this: I gave the order, 'At the third blow you will raise your hands, at the fifth you will lower them, at the sixth you will look foolish, at the ninth you will walk about the room, and at the sixteenth you will go to sleep in an easy-chair.' She remembered nothing at all of this on waking, but all these actions were performed in the order desired, although during the whole time Lucie replied to questions that were put to her, and was not aware that she counted the noises, that she looked foolish, or that she walked about. "After repeating the experiment I cast about for some means of varying it, in order to obtain very simple unconscious judgments. The experiment was always arranged in the same way. Suggestions were made during a well-established hypnotic sleep, then the subject was thoroughly wakened, and the signals and the actions took place in the waking state. 'When I repeat the same letter in succession you will become rigid.' After she awoke I whispered the letters, 'a,' 'c,' 'd,' 'e,' 'a,' 'a.' Lucie became motionless and perfectly rigid. That shows an unconscious judgment of resemblance. I may also cite some examples of judgments of difference: 'You will go to sleep when I pronounce an uneven number,' or 'Your hands will revolve around each other when I pronounce a woman's name.' The result is the same; as long as I whisper even numbers or names of men nothing happens, but the suggestion is carried out when I give the proper signal. Lucie has therefore listened unconsciously (subconsciously), compared, and appreciated the differences. "I next tried to complicate the experiment in order to see to what lengths this faculty of an unconscious (subconscious) judgment would go. 'When the sum of the number which I shall pronounce amounts to ten you will throw kisses.' The same precautions were taken. She was awakened, forgetfulness established, and while she was chatting with other people who disturbed her as much as possible, I whispered, at quite a distance from her, 'Two, three, one, four,' and she made the movement. Then I tried more complicated numbers and other operations. 'When the numbers that I shall pronounce two by two, subtracted from one another, leave six, you will make a certain gesture'―or multiplication, and even very simple divisions. The whole thing was carried out with almost no errors, except when the calculation became too complicated and could not be done in her head. There was no new faculty there, only the usual processes were operating unconsciously (subconsciously). "It seems to me that these experiments are quite directly connected with the problem of the intelligent performance of suggestion that appears to be forgotten. The facts mentioned are perfectly accurate. Somnambulists are able to count the days and hours that intervene between the present time and the performance of a suggestion, although they have no memory whatever of the suggestion itself. Outside of their consciousness there is a memory that persists, an attention always on the alert, and a judgment perfectly capable of counting the days, as is shown by its being able to make these multiplications and divisions." The experiments of E. Gourney confirm the same truth―that behind the primary upper consciousness a secondary lower consciousness is present. "P-ll," writes E. Gourney, "was told on March 26th that on the one hundred and twenty-third day from then he was to put a blank sheet of paper in an envelope and send it to a friend of mine whose name and residence he knew, but whom he had never seen. The subject was not referred to again till April 18th, when he was hypnotized and asked if he remembered anything in connection with this gentleman. He at once repeated the order, and said, 'This is the twenty-third day―a hundred more.' "S. (hypnotizer). How do you know? Have you noted each day? "P——ll. No; it seemed natural. "S. Have you thought of it often? "P——ll. It generally strikes me early in the morning. Something tells me, 'You count.' "S. Does that happen every day? "P——ll. No, not every day―perhaps more likely every other day. It goes from my mind. I never think of it during the day. I only know it has to be done. "He was questioned again on April 20th, and at once said, 'That is going on all right―twenty-five days'; and on April 22nd, when in the trance, he spontaneously recalled the subject and added 'Twenty-seven days.' After he was awakened (April 18th), I asked him if he knew the gentleman in question or had been thinking about him. He was clearly surprised at the question." The hypnotic self knew he had to do something, knew the particular act and the precise day when he had to perform it; watched the flow of time, counted the days and all that was going on, without the least intimation to the consciousness of the waking personal self. E. Gourney then conceived the happy idea of further tapping the intelligence and knowledge of this subwaking hypnotic self by means of automatic writing. "I showed P——ll," says E. Gourney,7 "a planchette*―he had never seen or touched one before―and got him to write his name with it. He was then hypnotized, and told that it had been as dark as night in London on the previous day, and that he would Le able to write what he had heard. He was awakened, and as usual was offered a sovereign to say what it was he had been told, and as usual without impunity to my purse. He was then placed with his hand on the planchette, a large screen being held in the front of his face, so that it was impossible for him to see the paper or instrument. In less than a minute the writing began. The words were, 'It was a dark day in London.' "When asked what he had written, he did not know. He was given a post-hypnotic suggestion to poke the fire in six minutes, and that he should inform us how the time was going, without any direction as to writing. He wrote soon after waking, 'P——ll, will you poke the fire in six minutes?'" To prove decisively the intelligence of the secondary, sub waking, hypnotic self, Gourney gave the entranced subject arithmetical problems to solve, and immediately had him awakened. When put to the planchette the subject gave the solution of the problem, without being conscious as to what he was doing. It was the hypnotic self who made the calculation, who solved the arithmetical problem. W——s was told to add together 5, 6, 8, 9, and had just time to say "5," when he was awakened in the fraction of a second with the words on his lips. The planchette immediately produced "28." P——ll was told during trance to add all the digits from 1 to 9; the first result was 39, the second 45 (right). Rehypnotized, and asked by S. what he had been writing, he said, "You told me to add the figures from 1 to 9 = 45." "Did you write it?" "Yes, I wrote it down." W——s was hypnotized and told that in six minutes he "as to blow a candle out, and that he would be required at the same time before this to write the number of minutes that had passed and the number that had still to elapse. He was awakened, laughed and talked as usual, and, of course, knew nothing of the order. In about three and a half minutes (he was taken by surprise, so to say) he was set down to the planchette, which wrote, "Four and a half-one more." About a minute passed, and W——s was rehypnotized, but just as his eyes were beginning to close, he raised himself and blew out the candle, saying, "It is beginning to smell." Hypnotized and questioned, he remembered all that he had done; and when it was pointed out to him that four and a half and one do not make six, he explained the discrepancy by saying, "It took half a minute for you to tell me; I reckoned from the end of your telling me." S——t was told in the trance that he was to look out of the window seven minutes after waking, and that he was to write how the time was going. He was then awakened. This was 7:34⅓ P. M. I set him to the planchette, and the writing began at 7:34½ I did not watch the process, but when I stood holding the screen in front of his eyes I was so close to his hand that I could not help becoming aware that the writing was being produced at distinct intervals. I remarked that he was going by fits and starts, and seemed to have to pause to get up steam. Immediately on the conclusion of the writing at 7:40 he got up and drew aside the blind, and looked out. Examining the paper, I found "25, 34, 43, 52, 61, 7." Clearly he had aimed at recording at each moment when he began the number that had passed and the number that remained. The subwaking, suggestible, hypnotic being seems to he not a physiological automaton, but a self, possessing consciousness, memory, and even a rudimentary intelligence. Sphygmographic tracings of the radial artery seem to point to the same conclusion. Thus in the normal state, on the application of agreeable stimuli, such as perfumes, the curves become broader, the pulse slower, indicating a muscular relaxation of the heart; while on the other hand, if disagreeable or painful stimuli are applied, such as pricking, faradic or galvanic currents, ammonia, acetic acid, formaline, etc., the pulse becomes rapid, the "Rückstoss elevation," or the dicrotic wave, becomes accentuated, and even rises in height (in cases where the dicrotic wave is absent it reappears under pain), the heart beats increase, indicating a more frequent muscular contraction. If now the subject is hypnotized and made anæsthetic and analgesic, and agreeable and disagreeable stimuli are applied, although the subject feels no pain whatever, still the characteristics of the pain and pleasure curves are strangely marked, indicating the presence of a diffused subconscious feeling. Records of respiration and of the radial artery, or what is called pneumographic and sphygmographic tracings, bring out clearly the real nature of the subconscious. This is done in the following way: A simultaneous pneumographic and sphygmographic record is first taken of the subject while he is in his normal waking state. A second record is then taken, with the only difference that disagreeable and painful stimuli, such as faradic current or odours of ammonia or acetic acid, are introduced. The tracings will at once show the painful sensations of the subject. The curves will suddenly rise, revealing the violent reactions to the unwelcome stimuli.

If now the subject is thrown into a hypnotic trance and a third record is taken, we shall then have the following curious results: If disagreeable and painful stimuli are applied, and if analgesia is suggested, the subject claims that he feels no pain whatever. In his normal waking state the subject will strongly react, he will scream from pain, but now he keeps quiet. Is there no reaction? Does the subject actually feel no pain? Far from being the case. If we look at the pneumographic tracings we find the waves uniformly deep and broad, the respiration is hard and laboured; a similar change we find in the tracings of the radial artery. The pain feeling is there, only it is not concentrated; it is diffused. The upper consciousness does not feel the pain, but the subconsciousness does. The painful or uneasy feeling is diffused all over the organic consciousness of the secondary self.

_________ 1. Binet, On Double Consciousness. Vide

Binet, Sur les alternations de la Conscience, Revue Philosophique, v, 27, 1884.

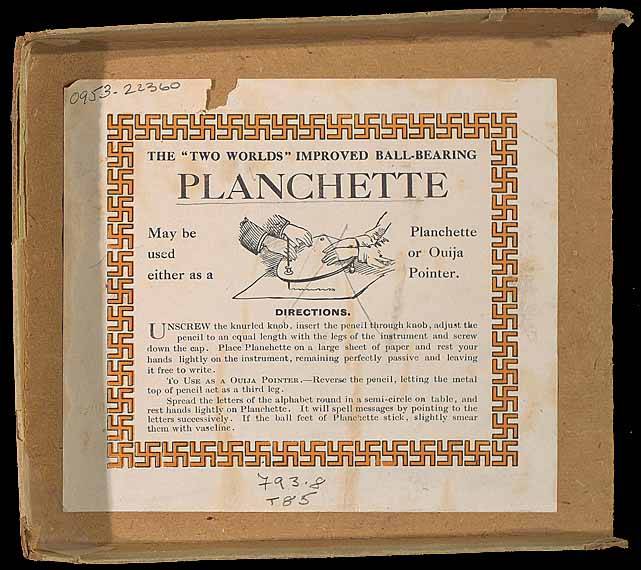

* "...a small triangular or heart-shaped board supported on casters at two points and a vertical pencil at a third and believed to produce automatic writing when lightly touched by the fingers; also: a similar board without a pencil."―Webster's "The board is supported by two castors and a pencil. When a person's fingers rest lightly on the board, it is supposed to trace words or drawings without conscious direction from that person. Spiritualists have used such devices to receive messages from the dead. "Unscrew the knurled knob, insert the pencil through knob, adjust the pencil to an equal length to the legs of the instrument and screw down the cap. Place planchette on a large sheet of paper and rest your hands lightly on the instrument, remaining perfectly passive and leaving it free to write."

|