| Boris

Sidis Archives Menu

Table

of Contents Next Chapter

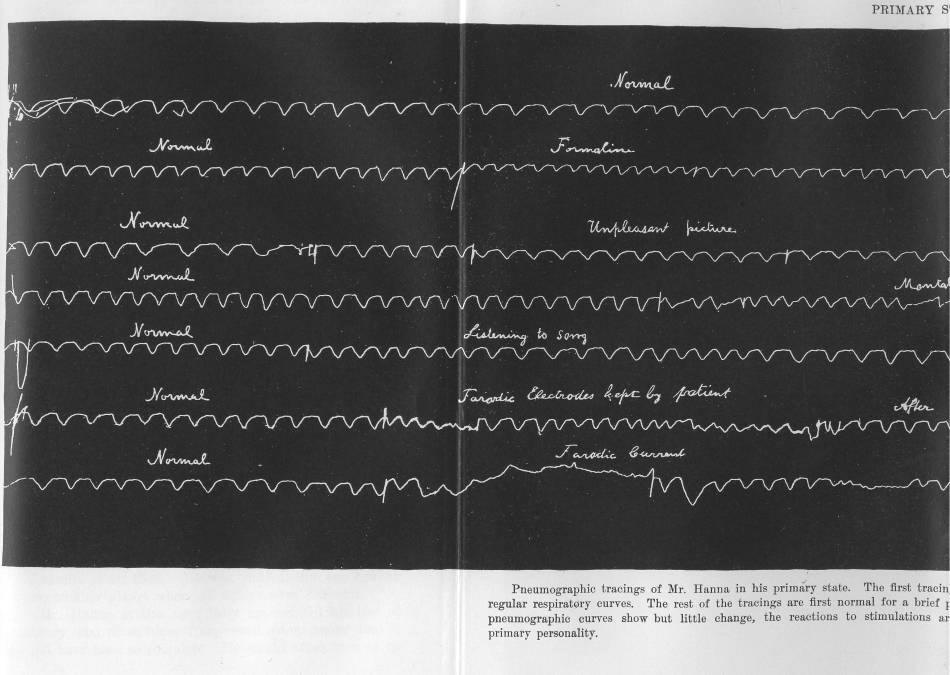

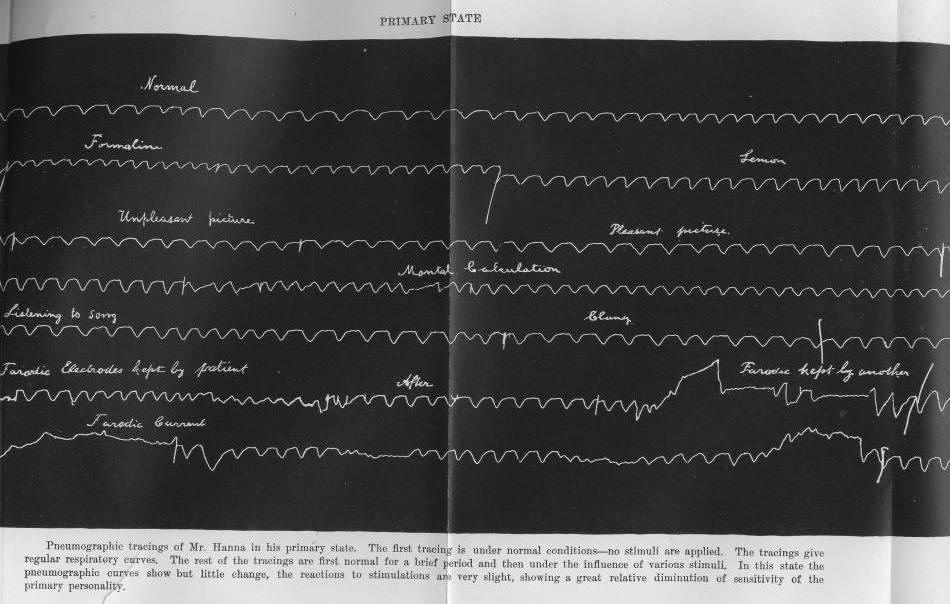

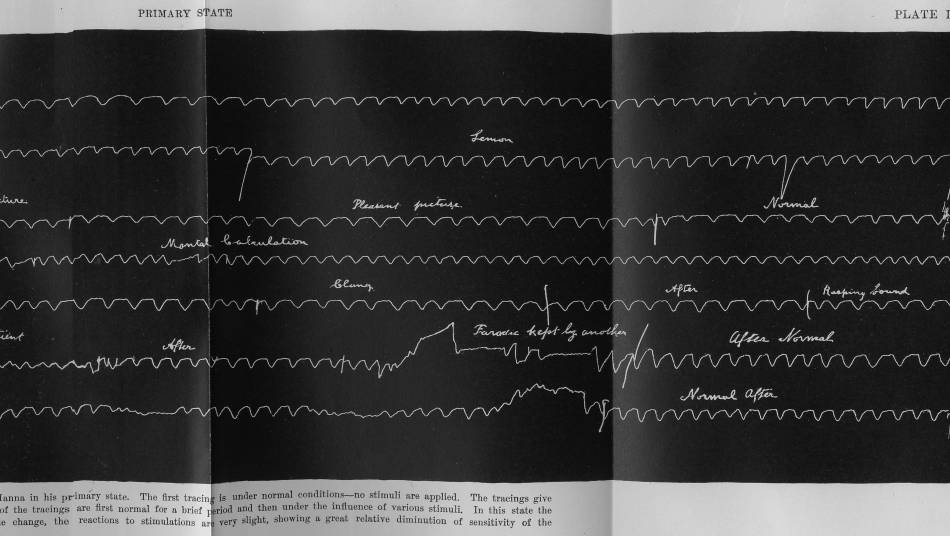

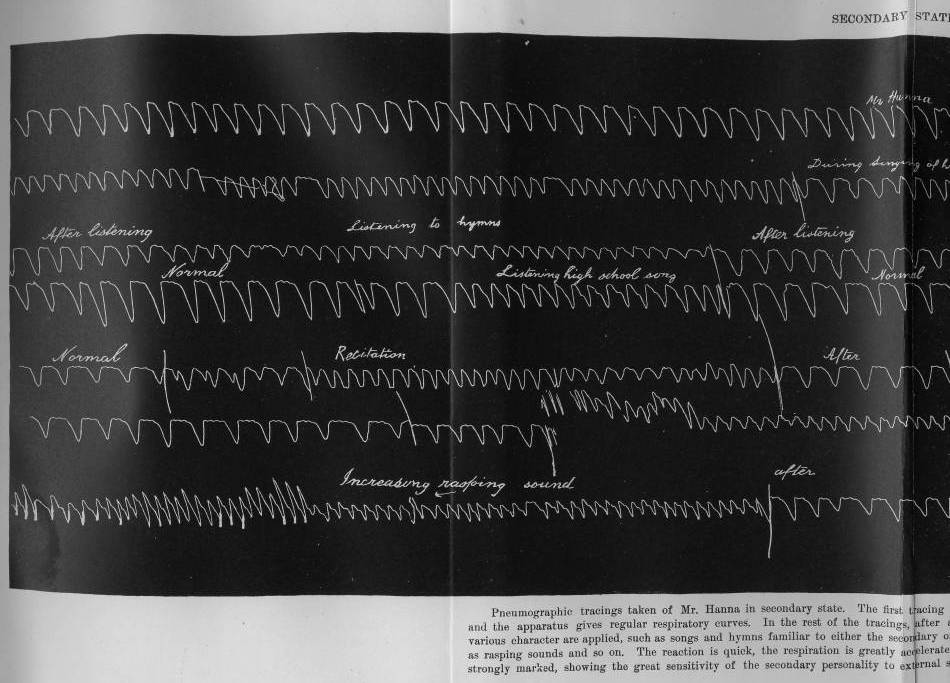

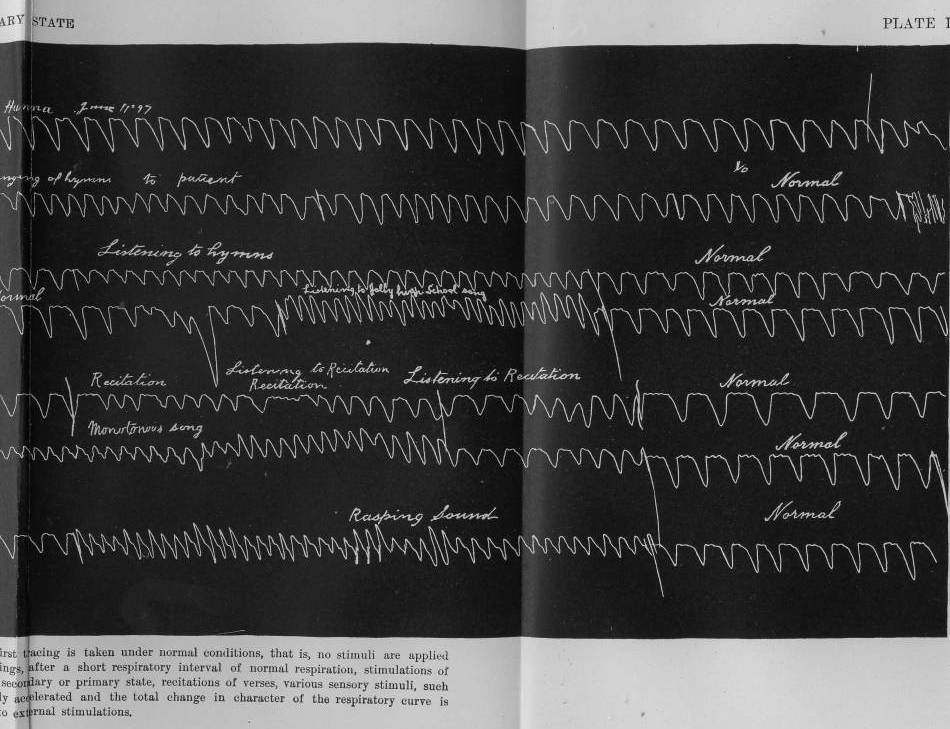

PART II CHAPTER XIV THE AROUSAL OF THE SUBCONSCIOUS THE next few days were spent in psychological experiments. With the pneumograph, sphygmograph, reaction recorder and other instruments, we studied the mental condition and the various reactions, sensory and motor, of Mr. Hanna in his several psychic states. During the following day Mr. Hanna remained in the secondary state. We wished to vary and intensify the stimulative agents, to reach if possible into the more susceptible recesses of his underground life and bring repeatedly to the surface memories buried within the subconscious. We must here emphasize the fact that the experiences used as psychic stimuli, in order to bring out repeatedly the primary state, were all of them of such a nature as to be similar to those of his former life experience, present in the subconsciousness. We avoided bringing him in contact with altogether new and sudden experiences which would act as a shock to him. Some of the experiences were similar to those already lived through by Mr. Hanna before the accident. Our efforts were in a general way directed along two more or less distinct lines. One, which we may appropriately term the method of recognition, consisted in the stimulation in each individual experience of a sense of recognition and of localization in some at least indefinite past. This method has rather an indirect value. Although Mr. Hanna had never direct recognition of objects, the sense of recognition was nevertheless stimulated, and finally the summation of the stimuli helped to bring out the primary state, of which it formed an essential element.

The second method, which may be termed that of psychic infusion, consisted in rapidly confronting him with new impressions, infusing, so to say, into his mind a mass of experiences which, although strange to his secondary state, were perfectly familiar to and even exact reproductions of events lived through in his primary state. The two methods were often conjointly applied. The second method was mainly used during the first evening preceding the full manifestation of the subconscious primary state. As an illustration of the first method, or that of recognition, we may describe our visit with Mr. Hanna to the Zoological Garden. Mr. Hanna before the accident had frequently visited the place and had been quite familiar with it. During our visit he displayed his usual intense interest and surprise. Everything seemed entirely new to him. To our question whether he had seen any of the animals, he invariably replied he had not. The only recognition he showed was indicated by the remark that he had seen a few weeks previously the picture of an elephant and rhinoceros in a picture-book. We passed a stall enclosing a donkey. Mr. Hanna at once exclaimed, “There is a horse exactly like that I saw in my dream.” Some of the more common horned animals he called cows, although evidently appreciating the differences. The deer was one of these. Some of the plumed birds he thought were a kind of chicks. We invariably observed that even the most commonplace things which he had not seen since the accident interested him greatly. He gazed at them with a curiosity as if he had never known them. He was like a child in his interest and amusement at seeing new objects, but showed his keen intelligence in inquiring and accepting critically statements about them. He was, indeed, like one coming from another planet where all things were different. Mr. Hanna at this time fully appreciated his loss of memory, and often himself expressed astonishment that it could have been so complete. He would often turn to us with the remark, “It is truly wonderful that I should have known (or lived through) such things before. I often try so hard to recall, but it is so impossible that I have about given it up.” As Mr. Hanna had not for several days passed into the primary state, and as we were anxious to induce alternation of the states as frequently as possible, we now, both for theoretic and practical purposes, employed the method of physiological stimulation. This method consists in the administration of some drug, which, without acting as a poison, stimulates the higher cerebral centres. The drug selected for this purpose was cannabis indica. The extract was employed and about two grains in one-fourth grain doses administered within four hours. The drug influenced strongly his circulatory system; the pulse became rapid; the rapidity increased decidedly when he moved about. There were no special sensory or motor phenomena manifested. His mind, however, remained clear, his intellect unaffected by the drug. His emotional state became gradually one of euphoria, and his actions soon indicated a sense of inner joyousness and mental buoyancy. He was mirthful; he seized pillows from the bed and threw them at his brother and otherwise showed an unusual playfulness. This condition gradually subsided and was succeeded by a state of calm, from which, after about half an hour, he passed into a natural sleep. Mr. Hanna was watched closely during the entire night. No phenomena of interest occurred. He was not in a hypnoidic state; when spoken to lightly, he did not reply, and reacted naturally to awakening stimuli. He continued in this secondary state during the night. At eight in the morning he awoke, looked about in astonishment, with no recognition of his new surroundings. (During the secondary state, we had intentionally changed his environment in order to keep him under the influence of varying stimuli.) Mr. Hanna did not recognize Dr. S., and looked at him in astonishment, although during the night, when he was in the secondary state, he had answered the questions of the doctor and fully recognized him. Dr. S. said to Mr. Hanna, “Do you know me?” Mr. Hanna replied, “No, I am sure I never saw you before.” Then Dr. V. G., whom Mr. Hanna knew and with whom he had had many conversations, came in; he likewise declared to have never seen him before. He knew nothing at this time of the psychological laboratory to which he had frequently been in his secondary state. In short, he knew nothing of events and persons since the first primary state. He remembered, however, everything that had happened up to the time of the accident and the events of the first primary state, and also what, in that first primary state, was told to him about the secondary state. Of the past few days, during which he had been in the secondary state, he had absolutely no recollection. The last thing he remembered was the room at Dr. G.’s house, and the conversation of the early morning (Tuesday), at which time he was in his primary state. Although it was now Saturday morning, when asked as to the day, Mr. Hanna said it was Wednesday. In his present state of mind, the consciousness of last events, time, place and circumstances of the primary state, was awakened and continued from the point left off. He at once noted the absence of Dr. G., whom he had met in the early morning of the 9th, when he was in the primary state. When asked how he rested during the night, he said he had slept well. When asked to arise and dress, he said he felt weak and wanted to remain in bed. His limbs were somewhat stiff, and he found some difficulty in moving them. “I feel,” he said, “a cramp in my knee,” pointing to the left limb, which was flexed. Examination of the extremity did not reveal any sensory or motor disturbances. He repeatedly remarked that he felt extremely weak, as if after some severe exhaustion. In conversation with Mr. Hanna, he was asked many details of his life up to the time of the accident. He gave exact accounts of them, showing a complete knowledge of his former life. He spoke of his university life, of his ordination as minister, of his experiences as a preacher, of his rescue of a woman in McKane County, Pennsylvania, during a severe storm in the mountains; he gave a description of his former friend Bustler; said that Bustler lived in Pottsville. In short, he gave a more or less complete biographical sketch of himself up to the time of the accident. Mr. Hanna, in his secondary state, had been reading “Lorna Doone.” In his present primary state, he was shown the novel and asked how much he had thus far read. He replied, “Why, I never read that book.”

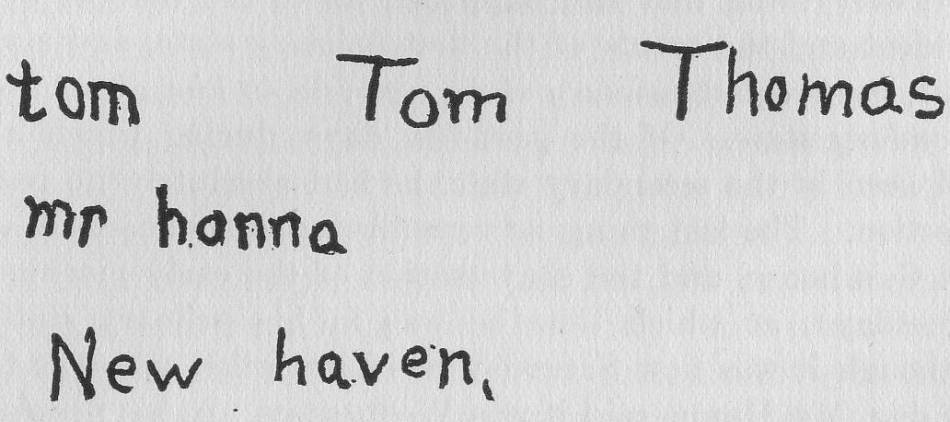

Fig. 20. Specimen of Mr. Hanna's writing in the secondary state.

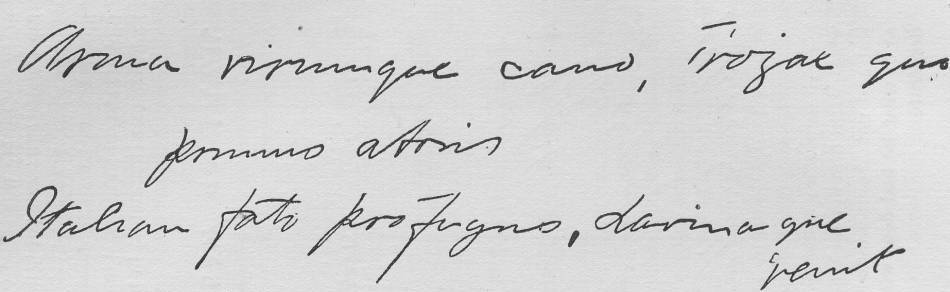

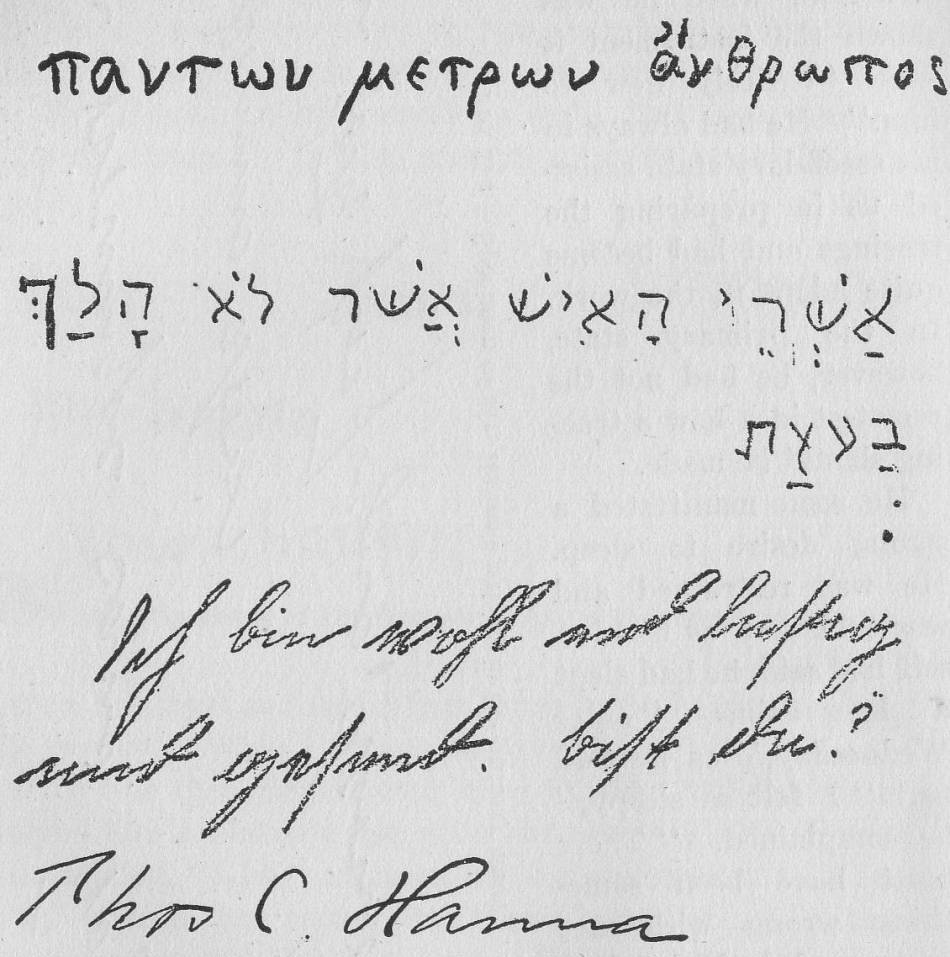

He was then asked about Miss C., who had faithfully nursed him for some weeks after the accident. Mr. Hanna now replied, “I have not seen her for nine weeks.” When asked at this time concerning Miss C., he did not become angry, as he did the first time. He now knew we were familiar with the events of his life. Mr. Hanna was then asked to write some sentences in English, Greek, German, Latin, Hebrew. (See reproduction of writing in each state, Figs. 21a, 21b.)

Fig. 21a. Specimen of Mr. Hanna's writing in the primary state.

Fig. 21b. Specimen of Mr. Hanna's writing in the primary state.

The sphygmograph was now produced in order to take pulse tracings. Although many tracings had been taken in the secondary state and he in that state had handled the sphygmograph and had carefully examined it and shown great interest in its construction, when he was shown the instrument it was “entirely new to him.” He had always in his secondary state assisted us in preparing the tracings and had become quite adept in the work. In the primary state, however, he had not the remotest idea how a tracing should be made. He soon manifested a strong desire to sleep. He was restrained and was told that, as he himself had said, he had slept a long time, “since Wednesday,” as he told us. “I felt so sleepy,” he complained. “There must have been something wrong with me; perhaps I had delirium and fever.” He was urged to overcome his inclination to sleep. Strong coffee and a good breakfast were given him to aid in prolonging the primary state. He was asked to dress and go out with Dr. S. for a walk, the intention being to prolong his present state. He showed great physical weakness and pain in his muscles. He began to dress himself slowly, but could not find his shoes; he was looking about for them in vain. (He had removed them while in his secondary sate, and now in his primary state could not discover their whereabouts.) This caused him much chagrin, as he was naturally methodical and not absent-minded. The total loss of all memory as to what he had done with his clothing made him fairly desperate. He did not desire to take a walk, and as Dr. S. did not wish to leave him alone and let him lapse into the secondary state, we continued the conversation. (In a discussion of the history of Indo-European languages.) Mr. Hanna showed great mental acuteness and familiarity with literature and history. He also showed remarkable keenness in discussing the question of ethics, or the nature of right and wrong, of good and evil. He expressed himself clearly, logically and forcibly. When the conversation turned on belles-lettres, on realism and idealism, Mr. Hanna displayed a wide range of reading. On the whole, he manifested a remarkable intelligence and versatility of mind trained by a university education. We see now that the primary state was a full reproduction, morally, intellectually and even physically, of Mr. Hanna as he was at the time of the accident. He was now overcome by an uncontrollable desire to sleep. His eyes began to close. He was urged to keep them open, but each time they seemed to drop in spite of his every effort. Dr. S. then endeavored to stimulate and arouse him. His limbs were moved violently, cold water was dashed in his face; he was pinched and otherwise mechanically stimulated. The onset of the somnolent state was irresistible. The lids closed; he could not control them. He fell into a state of unconsciousness. Every effort to keep him awake was futile. Even the mechanical opening of the lids did not bring response; he remained immovable. This state, which may be characterized as hypnoleptic, is of the highest importance both for theoretical and practical purposes. The nature of this state is discussed in another chapter. In this hypnoleptic state, Mr. Hanna was physically prostrated. He was like one dazed by a hard blow lapsing into unconsciousness. His muscular system was passive without the slightest rigidity. The conjunctival reflex was absent. There was absolute anaesthesia to touch and pain. He did not respond to the strongest, to the most intense and varied stimuli; nor did he react to loud shouts into his ears. He was evidently in a state of diffused, disaggregated consciousness.1 This hypnoleptic state continued for about a minute; The onset of this state, at first gradual, became rapidly more intense, and by a kind of accumulative force from moment to moment finally plunged him into complete physical prostration and mental isolation from the external world. The hypnoleptic state may be considered as an attack of sudden onset. It may be divided into two periods. The first is that of a rapidly increasing condition of extreme fatigue and of an overwhelming feeling of drowsiness, culminating in a second period, that of unconsciousness. A discussion of the two stages and their significance will appear farther on. After a lapse of about one minute, Mr. Hanna suddenly regained consciousness, opened his eyes and was found to be in his secondary state. He looked in surprise about him, wondered that he sat in a chair completely attired, and that his brother and Dr. S. were attending him. His last recollection was that of being in bed. He remembered distinctly, as he said, that he had retired, but he did not know how he happened to be fully dressed sitting comfortably in the chair. He felt exceedingly weak, and lay down upon the lounge. A condition of physical exhaustion, bordering on collapse, now superseded. He was cold, his skin was dry and pinched, the pulse was small, but not rapid. He complained of extreme cold. He found difficulty in moving his extremities. There was neither paralysis nor rigidity, nor was there catalepsy or negativismus. The arm passively raised dropped again inertly. Although fully conscious, as was evident from his appearance and from what he said afterward, he did not reply to questions put to him. When he was raised, he could not stand alone, but fell to the floor. In this condition, when touched, he seemed to be hyperaesthetic.

__________ 1 See Sidis, Psychology of Suggestion, chap. xx.

|