Fig. 1

Home Page Table of Contents Next Section

|

COLLISIONS IN STREET AND HIGHWAY TRANSPORTATION W. J. Sidis |

41. Traffic Interceptors. Those cities which have radial streets focusing upon one central point, are undoubtedly unfortunate. This arrangement tends to produce a few heavily travelled streets, circuitous routes, and congestion. The "square" arrangement of city streets seems unbeatable for efficiency and safety, and is fully adapted to artistic development. Curved streets are undesirable from a safety standpoint, although artistic design requires that curved boulevards be used in a city park system. In the latter case special efforts to secure a safe design must be made. For the city, a system of diagonal streets, sometimes referred to as "traffic interceptors," suitably spaced and at an angle of 45º from the main street grid, is efficient and can be made safe. The superposed diagonal street grid especially adds to the possibilities of artistic landscape architecture. The foci resulting from the introduction of the diagonal streets, should be parks or public buildings having no very large population. This suggestion is made in the interests of prevent mg congestion of vehicles parked upon the streets, or stopped for unloading and loading. The question of safety at these foci is discussed under "Special Intersections" (199), "The City Plan" (234) and "A Proposed Street Plan" (235).

42. Parking. The parking problem is probably the most salient of all the questions that confront users of motor vehicles, aside from the question of safety. Many cities have a parking congestion condition which is not only exasperating to vehicle drivers, but the time lost in hunting a parking space often offsets any gain which the mobility and speed possibilities of the vehicle provide. The increase in vehicle movements due to the searches for parking spaces, is undoubtedly reflected in increased traffic congestion.

43. Opposed Interests. The effect of parked vehicles upon the general question of street safety is not readily determinable, nor is the effect of parking restrictions upon merchants' business thoroughly understood. The battle is between the motor vehicle interests, who stand for liberal regulation, and the street car companies, who stand for close restriction. The issue is clouded by a number of conflicting features. One of these is the present unwillingness of owners of downtown real estate in large cities, to devote any space within the building lines to parking purposes. The evils which are found where all users of motor vehicles attempt to park at the curb wherever and whenever they choose, creates an imperative demand for a plan for the relief of downtown areas in large cities. Several suggestions for the solution of this problem follow.

44. Double Parking. "Double parking" is the unlovely child of the "parking evil." That this indefensible practice exists and continues to grow, is sufficient evidence of inadequate regulation. It produces dangerous situations upon the street, impedes traffic to an extraordinary degree and, considered merely from the standpoint of the motorist, should be prevented. It not only impedes traffic between intersections, and tends to nullify the advantages of progressive signal Systems, but frequently its obstructive effects are felt back at an intersection and then, of course, by practically all of the vehicles using or about to use the intersection. The remedy is for the traffic authority to observe which blocks or areas are persistently obstructed by double parkers, and to place restrictive measures upon parking in that block or area, which will substantially eliminate double parking. The application of the double parking test to the parking regulations for a given block, should certainly prove reliable and just.

45. Enforcing Regulations. Many cities find great difficulty in enforcing the parking regulations requiring that motor vehicles be permitted to stand in a given spot at the curb for only a specified length of time. The chances of being detected by a traffic officer are so small that the parker is often willing to pay an occasional fine; the fine being regarded as a storage charge. In general, this means that the curb space is occupied by many outlawed vehicles. This disregard for the regulations must be corrected before any progress can be expected. On the other hand, in order to be fair to the motor-vehicle operator, a drastic rule absolutely prohibiting parking should not be decided upon merely because of the difficulty in detecting the overtime parkers.

46. Rotational Parking. The following suggestion is offered as a means of actually limiting with reasonable certainty, the time a vehicle will be permitted to stand in one parking space at the curb. Upon any street which is to have a parking time limit, have the curb stone marked off into parking spaces of suitable length, twenty feet for example. These parking spaces are to be marked, perhaps by a method of painting upon the curb stone, into groups of four spaces; each one of the four to have a distinctive mark, 1, 2, 3, 4 for instance. A time cycle is to be chosen, based upon experience; and each of the parking spaces is expected to be vacated in turn for one-quarter of the total time of the cycle. If the total time of the cycle is two hours, then one of the four spaces will be vacated each half hour. The maximum parking time permitted here, would then be one and one-half hours. The parking inspector could ride down the street and note the registration numbers of the overtime parkers. In order to make reasonable allowance for errors in inspection, and to be equitable to persons unavoidably detained, a specified number of overtime cases might be allowed each operator each month. Excessive violators would be subject to revocation of their drivers' licenses after suitable warning. The author believes that somewhat longer periods than those now called for by the regulations might, in general, be permitted. The vacated spaces need not be wasted; they would be available to any vehicle for a brief time for loading or unloading.

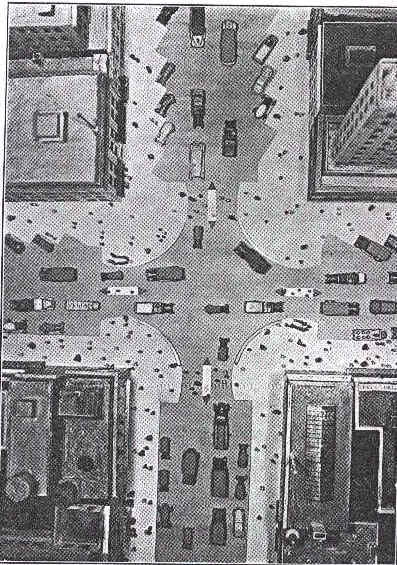

Fig. 1

Fig. 1 illustrates the rotational parking control plan. Considering the parking spaces nearest the curb corners as number 1, then these are all vacated first as shown. At the end of the quarter period, all of the number 2 spaces should be vacated and number 1 spaces would be available for parking for three-fourths of the cycle. Failure of the operators of vehicles in number 2 spaces to vacate, would be readily apparent to the parking inspector.

47. Angle Parking-Indented Curbs. In addition

to the question of time control of parking, Fig. 1 illustrates another idea in

connection with the parking problem. One-half of the picture is devoted to

parallel parking; the other half indicates an improved method of handling angle

parking. The reader is to understand that angle parking is not recommended, and

in the large majority of cases is highly detrimental to the best interests of

the public. However, where street space is available and the municipality is

satisfied that angle parking is best suited to a given situation, the indented

curb provides several advantages for the users of motor vehicles. Vehicles may

enter and leave without the interference often experienced with parallel

parking. Sufficient sidewalk space is available for passengers entering or

leaving vehicles, or for the handling of merchandise without occupying regular

sidewalk space. An increase of about 33 per cent in the number of parking

spaces will be obtained by the angle method. The principal drawback is the use

of additional street width to the extent of from six to nine feet on each side

of the street. The photograph indicates that the building lines are further

apart by about fifteen feet on the street having the indented curbing. Two

sizes of indentation are indicated. The spaces adjacent to the upper left

corner are for vehicles of smaller size; those adjacent to the upper right

corner are for somewhat larger vehicles. The questions of the size, or of the

variations in size adapted to any community, would be a matter for specific

planning. The angles of the indentations are about 30º from the axis of

the street. The aim in designing the indented curbs, and the control of the use

thereof should be, above all, to insure that the angle-parked vehicles

projected no farther from the normal curb line than the same vehicles would if

parked parallel. The photograph indicates two-way streets, but the ideas of

rotational parking and indented curbs are adapted to one-way streets equally

well. The photograph also shows the application to the safety intersection to be

described later, but rotational parking and indented curbs are also adapted to

streets having ordinary types of intersections.

49. Effect upon Pedestrians of Parking. Under the subject "Opposed Interests," (43) it was stated that the effects of vehicle parking upon street safety are not readily determinable. The reason for this statement is, that when vehicles are parked adjacent to intersections, the effect is to lessen the width of roadway available to running vehicles, and to permit pedestrians to "inch" out and move across the narrowed roadway with a somewhat greater degree of safety. The result of widening a street without the introduction of safety isles, or the effective widening by the removal of vehicles parked near the intersection cross walk, is to increase the hazard for pedestrians. This "inching" practice therefore represents a safety effort, but on the other hand, the cultivation of a bad habit in that the pedestrian is not keeping within designated bounds, the sidewalks. When the vehicle drivers also "inch" over the cross-walk, greatly to the interference of the free flow of the pedestrian streams, it is merely another step in the disintegration of control of the traffic units. Bad habits in one group encourage the same in other groups. The safety intersection to be described in subsequent paragraphs is intended to make it possible to clearly define the areas avail-able and safe for the pedestrians as well as the vehicles.

50. Combination-Use Buildings. Combination-use buildings look promising. If real estate interests can be persuaded, or economic pressure compels them to consider buildings having vehicle storage space along with other activities, there is little doubt that with their present knowledge, architects and traffic engineers will be able to design efficient combination-use buildings. An office building which had parking space in the central part of the first two or three floors, would provide the maximum of convenience for the tenants and patrons of the building. It is particularly desirable that the vehicle entrances and exits for such garage spaces should not require vehicles to be driven across the sidewalk. This suggestion is discussed more fully under "Under city sidewalks" (57), "Grade intersection elimination" (255) and "A proposal" (256).

51. Parking Garage Buildings. Parking garage buildings are being tried. They usually represent private investment; but the suggestion has been made that cities might well afford to build municipal garages for the public to use without charge, so that the streets would be freed of standing vehicles, to the advantage of moving traffic. There are several minor disadvantages associated with public garages. For the person who drives his own vehicle, there is a certain amount of incidental walking and of dead mileage.

52. Fees and Taxes. If a parking fee is required, there will be a class of owner-drivers who cannot well afford to include this fee in the daily cost of operating their vehicles. Parking garages are, however, well suited to the needs of those private automobile owners who hire chauffeurs. The questions of walking, dead mileage, and fees do not concern this class to an important degree. If a public garage is to be built by the municipality and operated with fees representing anything less than the true costs of construction and operation, some doubts will be entertained as to whether this will be entirely equitable to all taxpayers. The question of expediency seems to govern this case.

53. Exterior Appearance. The parking garage idea suggests that one city block out of eight, or seven, or six, etc., will be devoted to garage purposes; the ratio to increase as demand increases. The primary advantage of this plan is, that the space possibilities appear to be unlimited, whereas any other proposal for solution of the parking problem almost invariably has practical space limitations. The exterior appearance of the proposed garage blocks is likely to make them undesirable as close neighbors to retail stores.

54. Parking Squares. The use of vacant squares of publicly owned land for parking vehicles, would seem to be detrimental to the public interest, if located near homes or retail stores. The public will appreciate such land most if devoted to parks, playgrounds, etc.

55. Underground Parking. 56. Under Public Parks. Underground parking has been frequently suggested, especially for publicly owned land such as parks. The entire area of a public park might be excavated to form an underground garage, and then recovered with earth so as to restore the recreation and artistic features of the park. Two objections are apparent. One is the probable difficulty of rearing the larger trees essential to a beautiful park; the other is the question of the rental fee per car which would be required to make it unnecessary to tax the public for the construction and operating costs.

57. Under City Sidewalks. Underground traffic ways and parking space might conveniently be had under the sidewalks of city streets. To some, this plan may appear complicated, but to the author it looks quite feasible. The important points may be summarized as follows. It is essential: to provide a traffic way of sufficient width for one line of moving vehicles (about ten feet), as well as a parking lane of about ten feet; to provide sufficient head room and also have the underground traffic-way surface properly aligned with the building basement or sub-basement floor level; to properly care for the gas, electric, water, and similar service connections, and presumably to provide the pipe galleries for the longitudinal runs of most or all of these utilities; and to provide sufficient earth surface and volume for trees along the street at their customary locations.

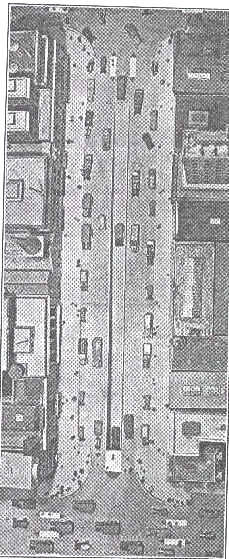

58. Ramps. Safe and convenient ramps or other devices for moving vehicles from the street level down to the underground level, must be provided, and particularly to do this without making it necessary for vehicles to cross the sidewalk as is now unfortunately the case where vehicles enter garages, gasoline stations, and terminal and loading areas. The method proposed by the author for having a ramp take vehicles from a traffic lane near the center of the street, is described more in detail in the proposed design which follows, and is applicable to the combination-use building plan, the garage block plan, and the underground parking and traffic ways. Fig. 2 illustrates the appearance of a street having the ramp.

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

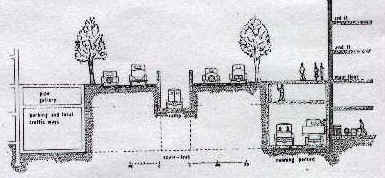

59. A Proposed

Design. Fig. 3 shows a vertical section

across the street, sidewalks, and buildings served by the underground traffic

ways. The running and parking lanes are each ten feet wide and twenty-two feet

below curb level. For a building having a sub-basement eighteen or nineteen feet

below curb level, there will be the convenience of loading motor trucks at floor

level. Where the building has no sub-basement, some alterations would be

required to secure access at the lower level, the installation of an elevator

for instance. Vehicles may enter the building where there is sufficient room to

receive them. The clear head room is shown to be about fourteen feet, but

traffic conditions may permit smaller dimensions in particular cases, and other

circumstances may require that both the twenty-foot width and the fourteen-foot

height be reduced in construction. On certain streets, narrow width, as well as

other circumstances, may indicate that a ten-foot moving traffic lane be

constructed, and that all vehicles be required to enter a building before

stopping, that is there would be no parking lane.

The pipe galleries, six feet high and twenty feet wide, should be ample for

all services except sewer. The ramp leading from street level to traffic-way

level, is shown. For any group of blocks, at least one ascending and one

descending ramp are required; more may be constructed if convenient and

economical. The position of the ramp requires the sacrificing of one

twelve-foot lane near the center of the street for a distance of about two

hundred and thirty-five feet or one short block. The ramp grade selected is six

per cent, but limiting conditions may require a steeper grade up to ten per

cent or more, in which case the exposed length of the ramp will be

correspondingly shortened. The steeper ascents are not recommended.

The blocks selected for a ramp should ordinarily have a width, curb to curb,

of at least fifty feet, and may be either one-way or two-way. Fig. 2 indicates a

one-way street. If, as is the case in certain blocks, it is permissible to

sacrifice the usual access to the curb for vehicles about to be loaded or

unloaded, the ramp may be placed at the curb line. The required street width,

curb to curb, would then be thirty to thirty-two feet. This arrangement would

apply to a one-way street only. The reduced design indicated might be used in

combination with the ten-foot underground traffic ways and, including the

elimination of the tree space, the idea might then be applied to a street having

a width of about fifty-five feet between building lines. If the ramp grade were

made ten per cent, in particular instances, and its use limited to the smaller

vehicles such as taxicabs, etc., the head room might be reduced to eight feet,

and the longitudinal loss of curb space would then be eighty feet.

The blocks selected for the ramps would be those where no

question of interference with street car lanes or prospective subway railroads,

would arise. Wide streets would be preferable; and short isolated blocks not

essential to long stretches of through-traffic streets, would be most suitable.

Blocks having grades are particularly well adapted to the construction of the

ramp.

The underground traffic ways and parking lanes are proposed

primarily for commercial vehicles, but they have important applications for

private motor cars, taxicabs, and buses. According to the author's proposal, the

underground traffic ways are intended to serve adjacent buildings and

underground parking spaces; they will be made as continuous as practicable

around the block or group of blocks served, but the proposal does not intend

that the ways are to be used by through or long distance traffic.

60. Midcity Buses for Downtown Transport. 61. Downtown Population Density. The centralization of industrial and commercial enterprise which has been the custom in cities and towns in every age, has rather firmly fixed the notion that the most favored conditions for city activities are associated with increased density of commercial and industrial populations. Street railways and suburban transportation systems, as well as railroads, usually aimed to deposit passengers near the heart of the city. The secondary question of transport between downtown points has frequently been a matter of pedestrianism, even along streets equipped with car tracks. The intensification of the street congestion problem in the central business districts of cities, resulting from the widespread adoption of the private motor vehicle, is familiar to all. Whether there is any obligation on the part of a municipality to permit the parking of private motor vehicles for extended periods upon the down town streets, or any obligation to provide off-street parking space, is a moot question.